Chapter 4: Test Your Grit

How do you measure grit? In all the studies we’ve mentioned, grit was quantified through a self-assessed survey. You can take it yourself and see how gritty you are.

You’ll see 10 statements. For each statement, choose a number from 1 to 5, depending on how much you identify with it:

5 = Not at all like me

4 = Not much like me

3 = Somewhat like me

2 = Mostly like me

1 = Very much like me

The 10 statements:

- New ideas and projects sometimes distract me from previous ones.

- Setbacks discourage me. I give up easily.

- I often set a goal but later choose to pursue a different one.

- I am not a hard worker.

- I have difficulty maintaining my focus on projects that take more than a few months to complete.

- I have trouble finishing whatever I begin.

- My interests change from year to year.

- I don’t consider myself diligent. I give up often.

- I have been obsessed with a certain idea or project for a short time but later lost interest.

- I don’t often overcome setbacks to conquer an important challenge.

Now add up your score - there’s a possible total of 50. Then divide that by 10. The higher your score, then the more grit you have.

How do you stack up against the population? Here are the different percentiles of grit across the population:

Percentile

Grit Score

10%

2.5

20%

3.0

30%

3.3

40%

3.5

50%

3.8

60%

3.9

70%

4.1

80%

4.3

90%

4.5

95%

4.7

99%

4.9

Grit has two components: passion and perseverance, and the questions actually correspond to both.

For your passion score, add up the odd-numbered items above. For your perseverance score, add up the even-numbered items.

Chances are, your perseverance score is higher than your passion score. People tend to be better at working hard than at maintaining a consistent focus. It’s easy to get attracted to a new idea. It’s hard to maintain that passion over a consistent period of time without giving up.

Because people have different scores, this suggests passion and perseverance are different things.

Rather than letting your interest be an intense burst of firecrackers that vanishes into vapor, let your passion be a compass instead, guiding you on a long winding route to your ultimate goal.

The Goal Hierarchy

People often have trouble figuring out what they’re aiming for in life. This is where people lack passion - they don’t care about what they’re doing all that much, and thus they tend to change what they like often, without committing to something.

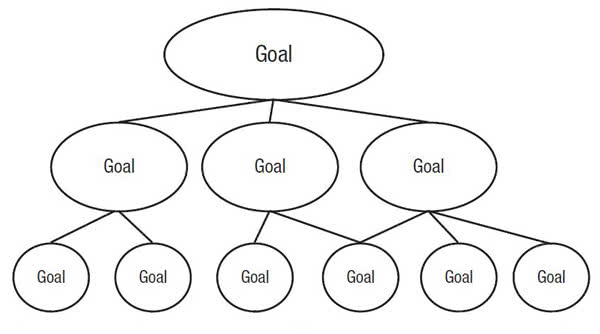

The book suggests framing your goals as a hierarchy, with multiple levels:

The low-level goals are your day to day actions – writing emails, going to meetings, jogging for an hour. We do these low-level goals as a means to an end of a higher-level goal – such as executing a project or looking good to your boss.

To figure out your higher-level goals, keep asking yourself, “why do I do this thing? Why do I care?” Each answer forms a progressively higher-level goal. At some point, you ultimately have no answer – you simply want to do something just because. This is your highest-level goal that is an end in itself. You can also consider it your "ultimate concern" or your compass.

This ultimate goal is what should drive every action at lower levels. If an activity doesn’t fit strongly within your goal hierarchy, then it likely isn’t moving you closer to your goal – and maybe you should stop. (For example, you might find that answering emails and hanging out on Slack all day isn’t actually helping you make real progress on your project, which then isn’t driving you toward a promotion.)

Once you have an ultimate goal in place, it’s something you almost obsess over. You’re loyal to the goal, not changing it on a whim. You go to sleep thinking about it, and you wake up thinking about it. This is your passion, and passion drives grit.

Properties of Good Goal Hierarchies

Once you understand your top-level goal, you can see that your low-level goals are merely in pursuit of the high-level goals.

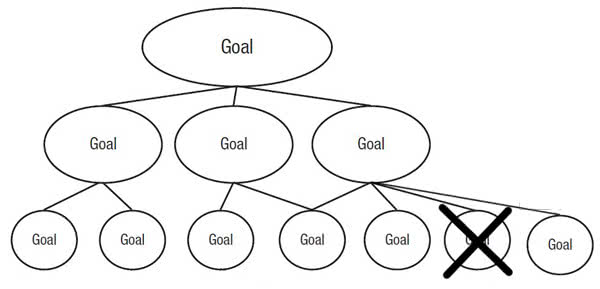

Low-level goals are not to be held sacred - they can be removed or changed. If you find a new low-level goal that is more effective or feasible or fun, you can swap it out for another. (Shortform example: If you find reading management books to be more effective than chatting on Slack, then you can swap the two as a low-level goal). This means you should reflect regularly on tasks you take for granted, and

Furthermore, this lowers how defeated you feel after failure. If you fail on a low-level goal, another can take its place. Lots of low-level activities can drive you toward your top-level goal. You have a lot of routes to getting there.

When well-constructed, a goal hierarchy promotes grit – if all your activities are in pursuit of your highest-level goal, then your everyday activities apply effort toward your goal.

Common Bad Goal Hierarchies

Here are common failings of goal hierarchies that lead to lower grit:

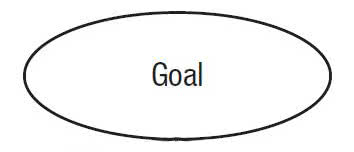

No lower-level goals

This person has a dream goal, like playing in the NBA or becoming a billionaire. But she hasn’t mapped out the lower-level goals that will get her there. This is "positive fantasizing" and makes it very difficult to achieve the goal.

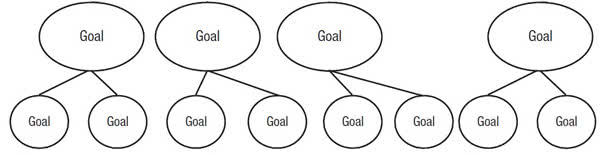

Mid-level goals without a top-level goal

This person has frictions between multiple goals, without a unifying theme. This makes it difficult to tell when goals are in direct conflict with each other, so some goals actually negate others. The absence of an ultimate goal may also make your energy feel purposeless. It may feel like spinning your wheels – applying a lot of effort without going in any particular direction.

If you feel pulled in too many directions, how do you prune your goal list? Warren Buffett suggests this exercise for prioritization:

- Write a list of 25 career goals.

- Circle the 5 highest priority goals for you. Only 5 - be strict with this.

- You must avoid the 20 goals you didn’t circle. These are your distractions.

If you can’t decide on 5, then consider quantifying your goals on two scales: interest and importance. Also, consider whether some of them contribute more to your ultimate concern than others.