Part 4: Choices | 1: Prospect Theory

Part 4 of Thinking, Fast and Slow departs from cognitive biases and toward Kahneman’s other major work, Prospect Theory. This covers risk aversion and risk seeking, our inaccurate weighting of probabilities, and sunk cost fallacy.

Prior Work on Utility

How do people make decisions in the face of uncertainty? There’s a rich history spanning centuries of scientists and economists studying this question. Each major development in decision theory revealed exceptions that showed the theory’s weaknesses, then led to new, more nuanced theories.

Expected Utility Theory

Traditional “expected utility theory” asserts that people are rational agents that calculate the utility of each situation and make the optimum choice each time.

If you preferred apples to bananas, would you rather have a 10% chance of winning an apple, or 10% chance of winning a banana? Clearly you’d prefer the former.

Similarly, when taking bets, this model assumes that people calculate the expected value and choose the best option.

This is a simple, elegant theory that by and large works and is still taught in intro economics. But it failed to explain the phenomenon of risk aversion, where in some situations a lower-expected-value choice was preferred.

Consider: Would you rather have an 80% chance of gaining $100 and a 20% chance to win $10, or a certain gain of $80?

The expected value of the former is greater (at $82) but most people choose the latter. This makes no sense in classic utility theory—you should be willing to take a positive expected value gamble every time.

Risk Aversion

To address this, in the 1700s, Bernoulli argued that 1) people dislike risk, and that 2) people evaluate gambles not based on dollar outcomes, but on their psychological values of outcomes, or their utilities.

Bernoulli then argued that utility and wealth had a logarithmic relationship. The difference in happiness between someone with $1,000 and someone with $100 was the same as $100 vs $10. On a linear scale, money has diminishing marginal utility.

This concept of logarithmic utility neatly explained a number of phenomena:

- This meant that $10 was worth more to someone with $20 than to someone with $200. This aligns with our intuition - people with more money are less excited than poorer people about the same amount of money.

- This explained the value of certainty in gamble problems, like the 80% chance question above. On a logarithmic scale for utility, having 100% of $80 was better than having 80% of $100.

- This also explained insurance - people with less wealth were willing to sell risk to the wealthier, who would suffer less relative utility loss in the insured loss.

Despite its strengths, this model presented problems in other cases. Here’s an extended example.

Say Anthony has $1 million and Beth has $4 million. Anthony gains $1 million and Beth loses $2 million, so they each now have $2 million. Are Anthony and Beth equally happy?

Obviously not - Beth lost, while Anthony gained. Yet Bernoulli’s model would argue they end up at the same utility and should be equally happy. Clearly the model is incomplete and can’t explain this.

Now let’s reset the scenario, giving Anthony $1 million and Beth $4 million again. Now we present Anthony and Beth with the following choice:

- 50% chance of ending with $1 million or 50% chance of ending with $4 million

- 100% chance of ending with $2 million

To try to explore the thinking yourself, imagine you’re Anthony, and you have $1 million. Which would you choose?

Now clear your head as best you can, and now imagine you’re Beth, with $4 million. Which would you choose?

If you chose different answers, you revealed the weakness in Bernoulli and expected utility theory. Option 1 has an expected value of $2.5 million, while Option 2 has an expected value of $2 million. According to these older theories, Option 2 should win every time.

But in reality, Anthony, with his lower money, is more inclined to choose option 2, while Beth is more likely to choose option 1. Anthony sees the certain doubling of his wealth as attractive, and would rather not leave it to chance that he ends up with no improvement. In contrast, Beth sees the certain loss of half her wealth as very unattractive. She would rather take the gamble to preserve her wealth.

Puzzling with this concept led Kahneman to develop prospect theory.

Prospect Theory

The key insight from the above example is that evaluations of utility are not purely dependent on the current state. Utility depends on changes from one’s reference point. Utility is attached to changes of wealth, not states of wealth. And losses hurt more than gains.

Consider that you probably don’t know your wealth to the nearest hundred, or even the nearest thousand. But the loss of $100—from an overcharge, or a parking ticket—is very acute. Isn’t this odd?

Consider these two problems:

You have been given $1,000. Which do you choose:

50% chance to win another $1,000 and 50% chance to get $0, or

Get an additional $500 for sure

You have been given $2,000. Which do you choose:

50% chance to lose $1,000, and 50% chance to lose $0

Get an additional $500 for sure

(Shortform note: if you’re in the fortunate position of having enough wealth so that these numbers aren’t very compelling to you, try multiplying them by 10x or even 100x, to get to a place where you think hard about the outcome.)

Note these are completely identical problems. In both cases you have the certainty of ending with $1,500, or equal chances of having $1,000 or $2,000. Yet you probably chose different answers.

You were probably risk averse in problem 1 (choosing the sure bet), and risk seeking in problem 2 (choosing the chance). This is because your reference points were different - from one point you were gaining, and in the other you were losing. And losses hurt more than gains, so you try to protect yourself against a loss.

Prospect theory seeks to explain all of the above.

Prospect Theory in 3 Points

1. When you evaluate a situation, you compare it to a neutral reference point.

- Usually this refers to the status quo you currently experience. But it can also refer to an outcome you expect or feel entitled to, like an annual raise. When you don’t get something you expect, you feel crushed, even though your status quo hasn’t changed.

2. Diminishing marginal utility applies to changes in wealth (and to sensory inputs).

- Going from $100 to $200 feels much better than going from $900 to $1,000. The more you have, the less significant the change feels.

3. Losses of a certain amount trigger stronger emotions than a gain of the same amount.

- Evolutionarily, the organisms that treated threats more urgently than opportunities tended to survive and reproduce better. We have evolved to react extremely quickly to bad news.

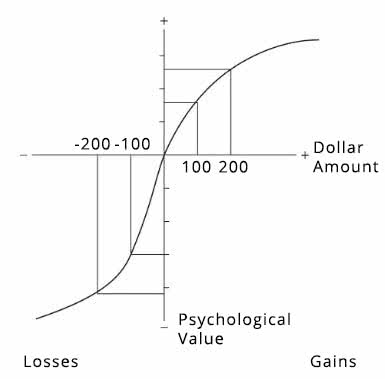

The master image of prospect theory is this:

The graph shows how psychological value changes according to the change in dollar amount. The middle of the two axes is the reference point—with no change, there is no psychological value. Psychological value is positive with positive dollar amounts (when you gain money) and negative with negative dollar amounts.

This graph was established through a host of experiments investigating how people perceive gains and losses, and how they trade off decisions like Anthony and Beth above.

Note two important properties of the curve shown:

- Diminishing marginal value: the curve isn’t a straight line on either end. The more money you gain, the less value each increment of money gives you. The same is true of losing money—losing $100 causes less anguish than 10x the anguish of losing $10.

- Loss aversion: the curve on the left of the y-axis has a steeper slope than the curve to the right of the y-axis. This signifies that the psychological pain of losing $100 is greater in intensity than the joy in gaining $100. Losses hurt more than gains do.

People have different curves, depending on their sensitivity to loss aversion. The ratio of slopes is called the “loss aversion ratio.” For most people, the ratio ranges between 1.5 to 2.5 - people would have to gain $200 to offset a loss of $100. In contrast, professional risk takers, like stock traders, are more tolerant of losses and have a lower loss aversion ratio, possibly because they have psychologically adapted to large fluctuations.

Revisiting Bernoulli’s Conundrum

Let’s revisit the scenario with Anthony and Beth. Anthony has $1 million and Beth has $4 million. They both have the following choices:

- 50% chance of ending with $1 million or 50% chance of ending with $4 million

- 100% chance of ending with $2 million

Anthony chooses the option 2, while Beth chooses option 1.

Prospect Theory now explains why. From the curve above, see that:

- For gains, 100% of 100 is larger than 50% of 200, because of how the curve flattens with more money. People are risk averse to get gains. Anthony would rather lock in a certain gain than risk getting nothing.

- For losses, 50% of -200 is less negative than 100% of -100. People are risk seeking to avoid losses. Beth would rather risk losing more if there’s a chance she keeps her money, than to have a certain loss.

While Bernoulli presented utility as an absolute logarithmic scale starting from 0, prospect theory calibrates the curve to the reference point. People feel differently depending on whether they’re gaining or losing money.